Isometric strength training is an interesting subject. It has an odd little history behind it and some of its popularity quickly faded when it was shown that it was not the golden goose that it was initially proposed to be. However, just because it didn’t yield the slightly outrageous results that it was initially proclaimed to produce, doesn’t mean it is not an effective training method.

Fatigue (Central vs Peripheral)

Thanks to my current job, I have been lucky enough to mess around with a bunch of cool, sports science training tools. One of the recent devices I have been playing with is called a Moxy Monitor. In short, it allows me to see the local metabolic demands of the muscle via anaylsis of muscle oxygen saturation levels “SmO2%” (amount of oxygen my muscles are using) and the changes in local blood flow.

Without diving too far into the science, the SmO2% can tell you how much oxygen is being released from the blood stream (capillary level) to the local tissue. The rate at which SmO2% is reduced (desaturated) and the rate at which it returns (resaturates) to baseline during exercise can provide some interesting insights.

As some may know, I am a velocity nerd. I think it is one of the most unique measuring tools available. So naturally, I wanted to use the Moxy Monitor in conjunction with a Tendo Unit to get an understand of how fatigue was manifesting itself during a velocity drop off squat session.

The Passive Spring

Storing and utilizing elastic energy is not only an intrinsic neuromuscular quality, but a skill. It requires the proper tensioning and timing of strong structural and contractile properties, which in turn allows them to store and realize the kinetic forces acting upon the body during the amortization phase of the jump. In other words, proper skill and strength allows you to act more like a bouncy ball when you hit the ground and less like a sack of potatoes.

Image 1

Jump Height and Absolute Strength: An Indirect Relationship

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

One of the most commonly talked about topics in strength and conditioning is the role that maximal strength plays in performance and whether or not it is necessary.

Before I dive into this topic, let me get some of the confusion out of the way. Maximal strength is not only important for performance, but it is mandatory. Without some level of maximal strength, there is no way any effort of great power could ever be performed.

Continue reading “Jump Height and Absolute Strength: An Indirect Relationship”

Explosive Strength Development

Figure 1: (Left Graph) relationship between load and percentage of 1rm. (Right Graph) An example of a force-time curve depicting how different elementary qualities are expressed with different external loads. Graphs are modified from “supertraining”

Explosive strength is not an independent quality, meaning there is no specific exercise that directly trains all of the components involved in its production. Instead, it is comprised up of four “elementary qualities” (listed below and in figure 1). These elementary qualities are independent of each other and must be developed through separate means. Together, they form the expression of explosive strength.

-

Maximal Velocity (Vo)

-

Starting Strength (early stage rate of force development) (SS)

-

Acceleration Strength (late stage rate of force development) (AS)

-

Maximal Strength (So)

How to Organize Plyometrics into Your Workout

AUTHOR : ALEXANDER BELL-MORATTO

Plyometrics are probably the most interesting part of athletes workouts. Or at least, the flashiest. It’s alluring to think that trying an advanced secret variation of an explosive jump that you saw on a youtube video of an MMA fighter (or professional dunker, or any other high level athlete) will morph you from Clark Kent into Superman.

Continue reading “How to Organize Plyometrics into Your Workout”

Force-Velocity Profile Builder

A ready to go force-velocity profile builder. Feel free to download and use.

Future book with Matt Van Dyke will cover application and utilization of some of these methods in much greater detail.

Max-Schmarzo-strongbyscience-F-V-profile-builder-Update-December 4

Rate of Force Development (Early versus Late)

Rate of force development (RFD) can be broken down into two stages. There is an early stage rate of force development and a late stage rate of force development. Early stage RFD is typically measured from 0-100 ms while late stage RFD is anything after.

Importance of Early Stage RFD

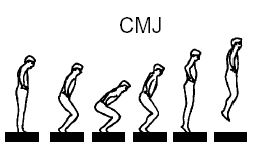

Sporting movements are often required to be fast, reactive movements that occur over a small amplitude. For example a large countermovement jump can take between 500-1000ms, while a squat jump with no countermovement may take around 300 to 430ms (1). In sport, movement amplitude is going to be much more similar to that of a squat jump (zero to minimal countermovement) than to that of a large CMJ. At the same time, sprinting ground contact times can last as short as 100ms. With this in mind, it is easy to see how early RFD may play an important role in sporting movement, especially those covering a small amplitude over a short period of time (ranging from 100-430ms).

Continue reading “Rate of Force Development (Early versus Late)”

Muscle Slack

Frans Bosch has popularized the concept of muscle slack (Van Hooren has publications on it). It is hinges on early stage rate of force development and the speed at which the muscle, tendon, and series elastic element can go from “slack” to “tense”. When a muscle is not activated, it is relaxed and there is slack in the muscle, tendon, and series elastic element as it hangs from its origin and insertion. Bosch uses the analogy of a rope to help describe how muscle slack works. You are holding one end of the rope and the other end is tied to a car, you are the origin and the car is the insertion. Before you can pull the car with the rope, the rope first has to become tense. This is the point where the rope goes from lying slack on the ground, to now in a straight line from your hands to the car. This is synonymous with the process of the muscle fibers aligning from the origin and insertion. The second part of the slack is that the rope now needs to become tense enough so that force can be applied to the truck. At this point, the rope goes from being in a straight line from your hand to the car, to now taut, from you producing a force on the rope. This is synonymous with the muscle co-contracting to produce enough force on the tendon so the muscle can become tense. Muscle slack uptake occurs during start of where the contractile element receives the chemical signal to align all the way to the point where both the musculotendon unit and the series elastic element are tense.

Muscle Slack and High Velocity Training: An Integrative Approach

Velocity Deficient

The idea of measuring and training for velocity deficiencies has become popular since the recent studies of JB Morin and colleagues. In one of their studies, they examined several different subjects and based on their profiling methods, determined whether or not the individuals had a force-velocity profile that was either velocity deficient or force deficient. Once the deficiency was determined, the subjects were trained using specific methods emphasizing the velocity component of the movement (slow velocity for max force and fast velocity for speed of movement). After the study’s training cycle, J.B Morin and colleagues were able to show that the specific training methods, either slow or fast, improved vertical jump performance and overall balance of the subjects’ force velocity profiles.

Continue reading “Muscle Slack and High Velocity Training: An Integrative Approach”

You must be logged in to post a comment.